DO THIS, DON’T DO THAT

January 22, 2011 Leave a comment

A spot on Margaret Gilleo’s leaf-scattered lawn is part of First Amendment history.

As political signs of all stripes dominate the urban landscape from now until Election Day, it’s that battle site that secured the right of homeowners to express themselves in plywood and cardboard.

The battle bounced from Gilleo’s Ladue neighborhood all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which struck down the St. Louis County municipality’s ordinance that barred most signs.

Campaign signs dot the lawns on Maryland Avenue in University City, as Teri Beuttenmuller walks with her two charges, Grant and Peyton LaMartina. In 1994, the U.S. Supreme Court declared unconstitutional Ladue’s ban on most yard signs. Yet some municipalities still try to regulate campaign signs. Photo by Karen Elshout

Nearly 16 years since the decision, some municipalities still are catching up. For example, this month Jefferson City is reconsidering its ordinance that bars political signs unless they’re planted certain days before or after an election season.

And while political signs may only be one aspect of the biennial political

season, Gilleo said they still have their purpose in the pantheon of free speech.

“It’s pure speech,” Gilleo said. “There’s no body language, no emotion. It’s just what it says.”

A sign against war

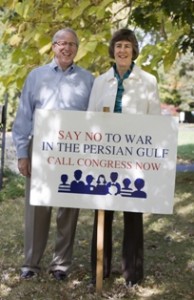

Gilleo’s legal odyssey began in 1990 when she placed a sign in front of her home stating “Say No to War in the Persian Gulf, Call Congress Now.”

After her sign was stolen and someone knocked a replacement to the ground, Gilleo alerted law enforcement officials. They told her such signs were prohibited in Ladue.

Gilleo, an instructor in Fontbonne University’s History, Philosophy and Religion department, went to Ladue’s City Council and asked for a variance, which was denied. She ultimately sued, arguing the ordinance denied her right to freely express her views on the conflict. While court proceedings churned on, the ordinance was amended to impede Gilleo from placing a sign in her window imploring others “For Peace in the Gulf.”

Gerald Greiman, a partner with Spencer Fane Britt & Browne who represented Gilleo in the case, said Ladue’s ordinance had two constitutional problems.

First, even though the ordinance was broad, it didn’t ban every sign and, Greiman said, was not “content neutral.” For example, the ordinance allowed for church signs or residential identification signs. Flags and signs showing that property was for sale also were allowed.

Margaret Gilleo, with her attorney, Gerald Greiman, shows a sign Ladue officials didn’t want her to display. Gilleo’s legal odyssey began in 1990 when she put the sign in front of her house. Photo by Karen Elshout

The second problem, he said, was that yard signs were a “distinct mode of speech” that can’t be banned on a wholesale basis.

After two lower courts ruled the ordinance was unconstitutional, Ladue officials appealed the matter to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a unanimous decision written by Justice John Paul Stevens, the court affirmed the lower court ruling and declared Ladue’s ban was unconstitutional.

Stevens wrote that the signs are “an unusually cheap and convenient form of communication.” He cited the economic convenience of a yard sign versus other free speech conduits.

“Especially for persons of modest means or limited mobility, a yard or window sign may have no practical substitute,” Stevens wrote. “Even for the affluent, the added costs in money or time of taking out a newspaper advertisement, handing out leaflets on the street, or standing in front of one’s house with a hand-held sign may make the difference between participating and not participating in some public debate.”

Stevens went on to say that most Americans “would be understandably dismayed” to learn that it was illegal to display from their window an 8-by-11-inch sign expressing their political views.

“Whereas the government’s need to mediate among various competing uses, including expressive ones, for public streets and facilities is constant and unavoidable … its need to regulate temperate speech from the home is surely much less pressing,” Stevens wrote.

‘War on signs’

Alan Howard, a law professor at Saint Louis University who specializes in free speech cases, said the Gilleo decision had a dramatic effect on municipalities’ ability to create wholesale bans on signs.

Howard said the court previously upheld prohibitions on posting political signs on public property for “urban blight” concerns.

“Ladue read that case more broadly to mean that the city had the authority in the name of aesthetics to ban signs generally,” Howard said. “They just basically declared war on signs.”

After City of Ladue v. Gilleo, Howard said, cities cannot ban yard signs just because they think “they’re aesthetically displeasing.”

“[Stevens] basically said even if the law was a total ban, prohibited any and all signs, we still would strike it down, even if it was content neutral,” Howard said. “[The court] would still strike it down, because we think it prohibits too much speech, just generally.”

Howard and Greiman both noted that the Gilleo decision didn’t completely usurp municipalities’ ability to regulate signs. For one thing, municipalities still can bar placing political signs on public property.

Stevens also wrote that “residents’ self-interest diminishes the danger of the ‘unlimited’ proliferation of residential signs that concerns the city of Ladue.”

“We are confident that more temperate measures could in large part satisfy Ladue’s stated regulatory needs without harm to the First Amendment rights of its citizens,” Stevens wrote.

Howard said the opinion gave municipalities leeway on regulating signs.

“So maybe you can regulate how many signs people can have,” Howard said. “At some point, they might say ‘enough’s enough.’ You can put up 10 signs, three signs. But you can’t let your front yard be taken over by a thousand signs.”

Still, Greiman said, opportunities exist for municipalities to overreach with regulation. For example, a regulation could prohibit someone from showing support for multiple candidates.

“I think there are probably some latent problems in a number of city ordinances in the way they go about trying to restrict the number of signs,” Greiman said. “I think what’s reasonable in a particular context may depend on an election season or how many candidates or issues are on the ballot.”

Catching up

Greiman said municipalities took “all different approaches all over the map” after the Gilleo decision.

“We saw some cities really try to take the decision to heart, and try to amend their ordinances to comply with the court’s opinion,” Greiman said. “We’ve seen cities do nothing. We’ve seen cities just back off in terms of how they might enforce the ordinances on the book but not really take steps to formally modify the ordinances.”

Some cities, he added, repealed their bans and didn’t try to replace them with anything.

John Mulligan Jr., the city attorney for University City, said his municipality has a “lengthy” sign ordinance.

“We do, pursuant to the First Amendment, regulate signs — time, place and manner,” Mulligan said. “We had correspondence with the ACLU about our sign ordinance, as I recall. There were communications on it, and from what I understand, they had no objections on constitutional grounds to our ordinance by the time it was passed.”

Some communities around the state still are angling to update their ordinances. Nathan Nickolaus, the city attorney for Jefferson City, said his municipality still has an ordinance on the books that could fall short of constitutional muster.

“The general rule is no temporary signs and no signs in residential areas,” Nickolaus said. “Ours is a very typical ordinance. What it says is you get to have a political sign 30 days before the election until seven days after the election. So only during a specified period of time and only what it specifies as ‘political signs.’”

Nickolaus said that type of regulation generally has been found not to meet constitutional standards, and thus his office is not enforcing the ordinance. The most obvious problem, he said, is that ordinance is content-based and excludes religious signs.

“To put it a different way, you can have a sign that says ‘Vote for Joe,’ but not a sign that says ‘Vote for God’ or ‘Pray for the Troops,’” Nickolaus said.

He also said prior court cases found banning signs except for certain time periods was constitutionally questionable.

“The reasoning the courts have applied on that is, let’s say you’re against the war or some other issue that’s not necessarily a campaign issue,” Nickolaus said. “You’re essentially excluded from your message coming out at an appropriate time.”

In seeking to amend the current ordinance, Nickolaus said one of his difficulties as an attorney is informing Jefferson City’s City Council on what they can and can’t do in regard to sign ordinances.

“In fact, I got messages from several of them saying, ‘We’re OK if you want to say ‘Support the Troops’ or ‘Merry Christmas,’ as long as they don’t allow this other kind of stuff,’” Nickolaus said. “Well, that’s not the way that the Constitution works. You don’t get to pick which messages people can have.”

Full circle

The Gilleo case came back to affect Gilleo and Greiman in their personal lives.

Gilleo said she met her future husband, Chuck Guenther, after he wrote a letter to her about the case. She said the case was one of the most “expensive personal ads” ever, as it took the launch of a war and high-stakes legal clash over free speech for the two to meet.

And after defending in the courtroom the right to use political signs, Greiman is getting an up-close lesson about how signs influence the political process.

Greiman’s wife — Susan Carlson — is a Democrat campaigning for a St. Louis-area state representative seat. He said he has talked with political advisers about the value yard signs add to his wife’s campaign.

“Some people will tell you they’re very important; some people will tell you they’re not worth the money they cost,” Greiman said. “Typically, state rep campaigns don’t go on radio or TV. And so, yard signs are a big part of it, especially for local elections.”

“The fact is — and there’s good literature on this in some of the political strategy books — yard signs are really recognized as a very uniquely effective and inexpensive mode of expression,” Greiman said.